Official Website of JAN CZOCHRALSKI, Forefather of The Silicon Era

As a child, Fred Schmidt heard the stories about his grandfather, Jan Czochralski, who at one time was considered a genius and a hero in his native Poland and across Europe. The realization of just how important he was, though, didn’t set in for Schmidt until much later in life after he realized that the technology that surrounds our lives — laptops, mobile phones, autonomous cars, spaceships, solar cells, and almost all things tech — depends on a method his chemist grandfather discovered in 1916 to produce single silicon crystals. It is still known as the Czochralski — or CZ — method and is the foundation for producing 95% of the world’s chips that run semiconductors and integrated circuits, the hearts and brains that power our connected world.

The jewelry industry also uses his “crystal-growing” technique to create synthetic gemstones like cubic zirconia, diamonds, rubies, sapphires, and more.

“Here was a man that went from being heralded as one of Poland’s greatest scientists to finding himself contending with the brutality of the Nazis and then ushered into obscurity by the Soviet communists,” Schmidt says. “He was finally rediscovered in Poland around 2011, and while he is known worldwide by much of the academic and scientific communities, for most Americans and Europeans his achievements have been buried by time and a shroud of communist secrecy in the decades since he died in 1953.”

That quiet around the achievements of someone who should be heralded as a scientific giant compelled Schmidt to assert his grandfather’s legacy among other Polish scientific greats like Marie Sklodowska-Curie, who won the Nobel Prize twice, and mathematician and astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus. “Czochralski is too hard for English speakers to pronounce, and I’m a marketing guy, so I figured JanCZ had a good ring to it for the English-speaking world,” Schmidt says.

And so the JanCZ project was born; a project that encompasses funding and championing a feature film, documentaries, a website, books, scholarships, and even a history center that Schmidt, who calls Austin, Texas, home, wants to see housed in JanCZ’s last Polish home — the house Schmidt himself grew up in before he emigrated to the United States with his mother at age three.

Here was a man that went from being heralded as one of Poland’s greatest scientists to finding himself contending with the brutality of the Nazis.”

Joining him in his efforts is JanCZ’s great grand nephew, Sylwester Czochralski, who works in finance for a Danish tech company in Warsaw. “JanCZ faced considerable challenges throughout his life,” Czochralski says. “He struggled with limited resources for scientific research, particularly in partitioned Poland, and later, during the communist era. That meant his legacy was not as widely acknowledged as it should have been.”

Schmidt was born Klemens Jan Borys Czochralski, the son of JanCZ’s youngest daughter, Cecylia. He and his mother, emigrated from Poland via Canada to the Polish community of Hamtramck in Detroit as political refugees, where they were granted asylum by President Dwight D. Eisenshower. (Cecylia had two elder siblings, Elona, who also emigrated to the U.S. and settled in Detroit, and Borys, who never left Poland.) Schmidt went through four name changes by age 13 and soon lost his native tongue and accent as he assimilated into American culture during the Cold War. Schmidt eventually made his name as an entrepreneur building video game companies in the U.S. and Europe — the serendipity that success came in the field of technology is not lost on him. For the last decade he has been part of the International Relations team at Capital Factory, the largest accelerator and most active investor in tech startups and scaleups in the State of Texas.

JanCZ never got to see his work integrated into so many technical devices, since it wasn’t until 1958 — five years after his death — that emerging electronics scientists at Bell Labs and Texas Instruments in the U.S. came across his published papers and began applying the Czochralski Method in their creation of integrated circuits. It was first used in electronics, then, a short time later, it would prove fundamental to the rise of computing technology.

“It’s really sad because he should have been able to live to an old age comforted by the recognition he had among people in Poland and all over the world — and the income that would have gone along with that,” Schmidt says.

JanCZ was born in 1885 in the small town of Kcynia, then still part of the Prussian empire, in today’s western Poland. At the time of his birth he was officially a German citizen. He eschewed college, instead choosing to pursue his fascination with experiments in metallurgy in the back room of his parent’s home. JanCZ eventually moved to Berlin and found work at AEG, a prominent German electrical equipment manufacturer, researching the use of aluminum in electrotechnology as an ambitious and self-taught scientist and entrepreneur. A few years later he established his own laboratory of metal science in Frankfurt at age 32.

JanCZ never got to see his work integrated into so many technical devices

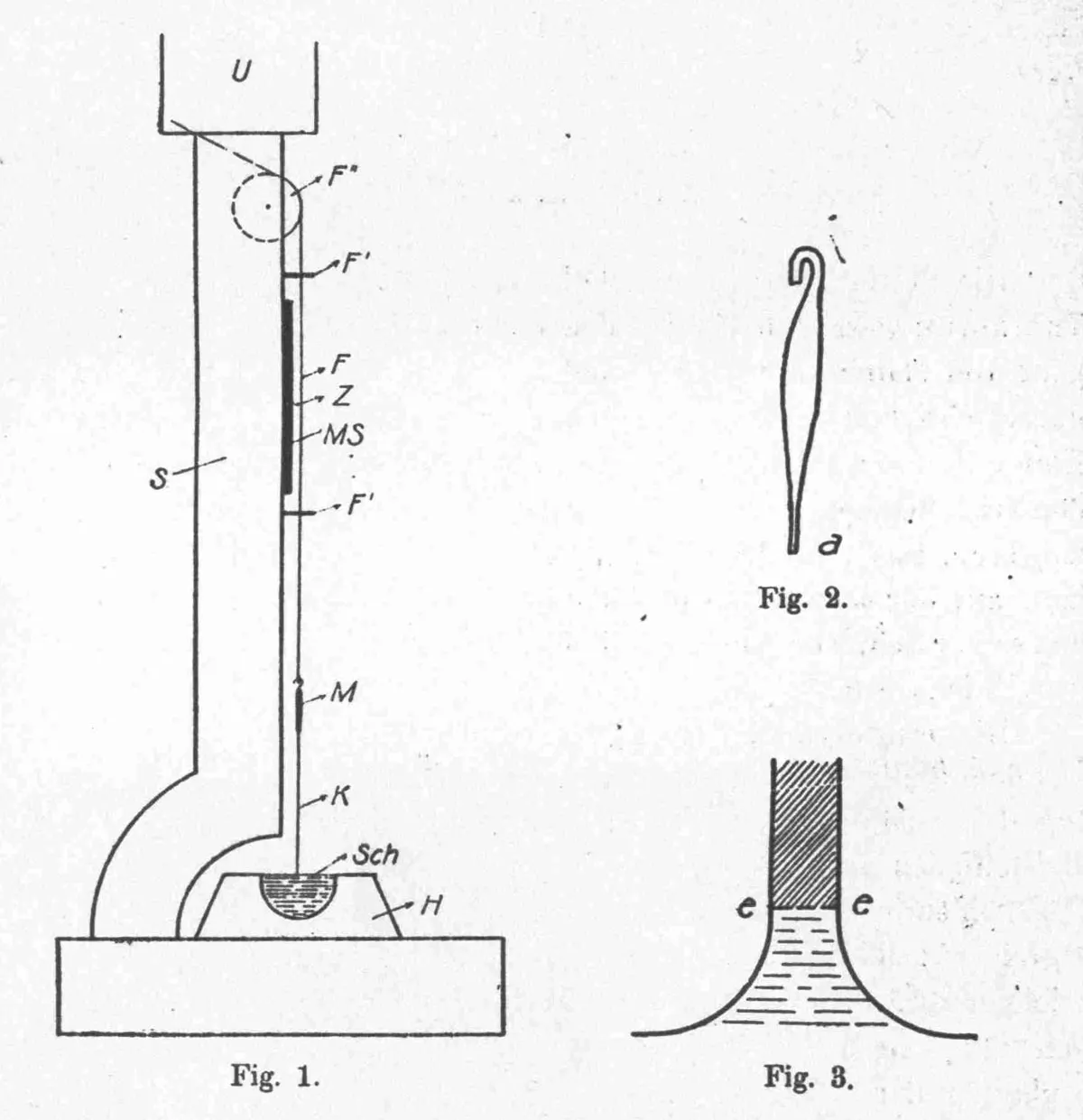

One day in 1916, after a tiring day in his lab working on metallurgy reports, he accidentally dipped his quill pen into a well of molten tin instead of ink. When he pulled it out, he noticed a long metal thread hanging from the nib. He repeated the accident and found the size of the thread seemed to depend on how quickly the nib was removed. JanCZ also discovered that his accident — which he wrote about more formally in a paper — also produced a single crystal (monocrystal.) Since most testing of metal properties at the time could only be done with a single crystal, JanCZ’s method was celebrated as a cheap and easy way to advance research.

JanCZ didn’t patent the method because to get a patent approved you had to provide a specific application of the invention, and he couldn’t identify a direct use for his technique. He certainly didn’t get rich from it. It was another discovery, of metal B in 1917, that would make him wealthy and famous; the alloy could be used in the nascent railroad industry — instead of costly and hard-to-obtain tin — for steel track parts which allowed trains to move faster. Henry Ford recognized JanCZ’s work, invited him to the United States, and offering him a research and development role at the Ford Motor Company, but he declined. Schmidt recalls: “My mother told me that at the time my grandfather said, ‘I have enough wealth, I have enough fame, my country Poland needs me now.’ And that was the fateful decision in his life, the fork in his road, that changed everything for him, and it did not end well.”

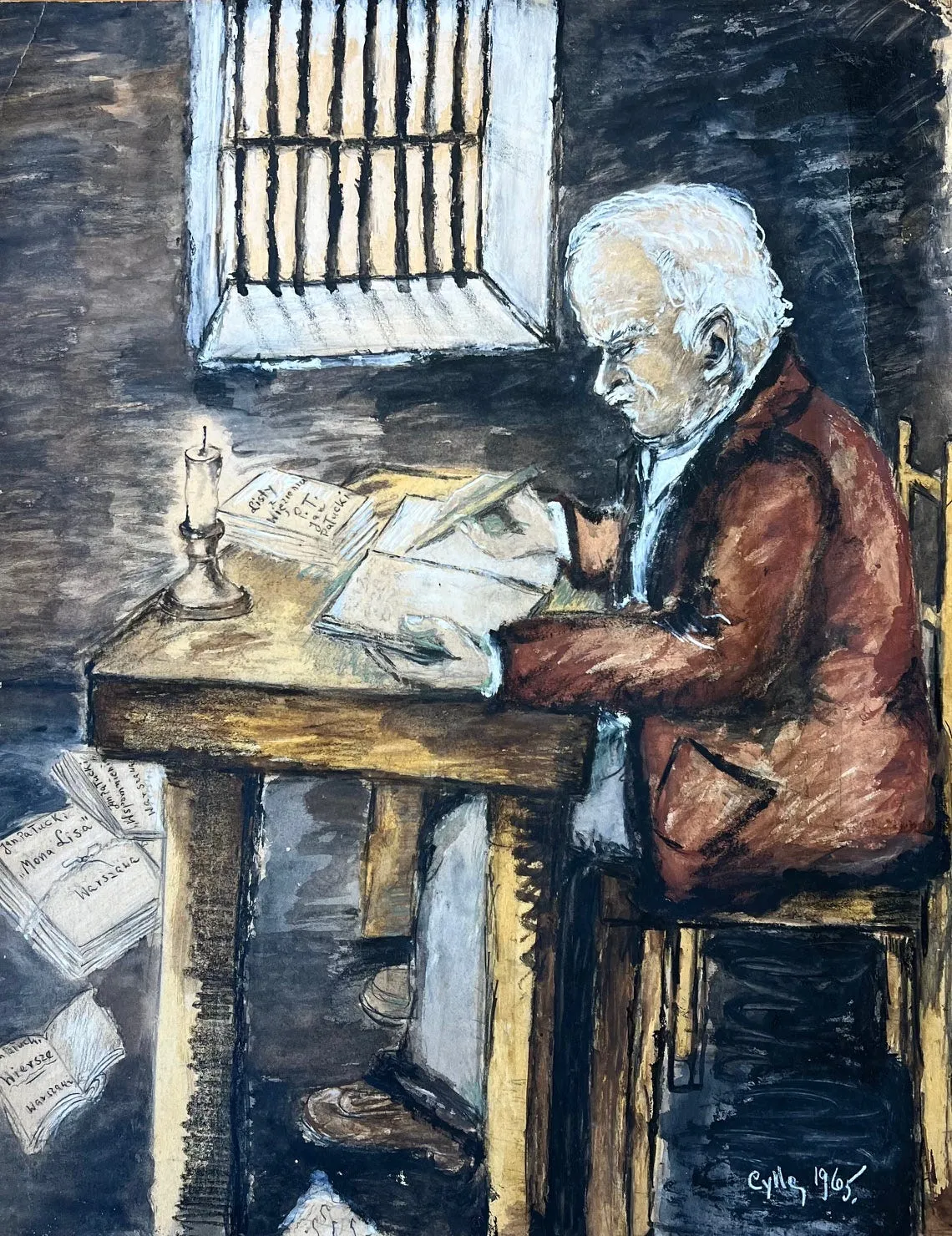

JanCZ married Marguerite Haase, an accomplished German pianist of wealthy Dutch descent, in 1910. In 1928 they moved to Warsaw at the invitation of Poland’s president Ignacy Mościcki, himself an accomplished chemist, and the two men became close. JanCZ flourished in a new life; he was awarded an honorary doctorate from Warsaw Polytechnic, now the Warsaw University of Technology, and served as Chair of the Metallurgy and Metal Science Department which was established for him. He evolved to be quite a Renaissance man, socializing with musicians, artists, and intellectuals, and even penning poetry under a pseudonym, Jan Palucki, all while making new scientific discoveries.

Henry Ford invited him to the United States and offered him a job in research and development, but JanCZ declined.

When the Nazis invaded Poland in 1939, JanCZ found himself in a tight spot. With his close German connections, he was able to navigate the dangers of being arrested or killed in the war, but was forced to use his laboratories for the benefit of Germany. His heart and loyalty, though, were always with the Polish people. The Germans never completely trusted him, and took his youngest daughter — Schmidt’s mother — to a labor camp as an “insurance” policy. JanCZ ultimately ended up using those connections to stop the imprisonment of many Poles and Jews, and helped support the production of munitions for the resistance movement. But navigating this complex web every day for more than six years would come back to haunt him: JanCZ was soon to have a new national overlord to contend with, one with whom he had no prior relationships to leverage in any way.

In 1945, as the Soviet Union was given control of Poland at the Yalta Conference, the communists charged JanCZ with collaborating with the Nazis, but he was unable to testify to his work with the underground resistance for fear it would give up his comrades in the movement. Witnesses to JanCZ’s commitment to Poland eventually helped clear him of the charges, which could have resulted in the death penalty, but by then his academic career was destroyed. Nearly all of his homes, valuable artworks, and possessions were seized by the Soviet regime and his honorary degree taken away.

The communists continued to harass and investigate JanCZ, who, along with his family, was banished from Warsaw back to his only remaining small home in Kcynia, Margowo, which he had designed and built for his wife. “That was the house I was born in,” Schmidt says. “It was there that the Soviet secret police dragged JanCZ away for the last time, taking him back to jail again in Poznan to interrogate him some more, and where he died of a heart attack at age 67.”

It wasn’t until the early 2000s that Poland began to hear JanCZ’s story. Professor Dr Pawel Tomaszewski, a Wroclaw scientist, penned many papers and books about the Czochralski method and, most recently, a 700-page biography in Polish of the inventor. He also petitioned the Polish government and Warsaw Polytechnic to review the assembled body of work he’d gathered and to recognize JanCZ and his powerful contributions to science — how important he was not only to Poland, but to the world.

When seeking relatives of JanCZ to interview for a 2014 Polish television documentary, Tomaszewski and a film crew met with Schmidt in Florida. “And that, after decades of my own ignorance, bombarded me back into my grandfather’s story,” Schmidt says. He ended up seeing the premiere of the film — directed by Sylwester Banaszkiewicz and produced by acclaimed Wroclaw-based media production house Media Brigade — at the Camerimage Film Festival in Bydgoszcz, and then toured his former home in Kcynia.

“Participating in this film suddenly made JanCZ very real for me,” Schmidt says. “Being interviewed on the topic of my family and grandfather for the first time was personal and emotional. In 50 years, no one had ever asked me about any of this before. My family history, and my Polish heritage really, was deeply suppressed and ‘unnecessary’ in my life. Now, suddenly, it started to mean something to others. And so I felt an obligation to be a voice in this important story for the benefit of modern society.”

Jan CZ’s grand nephew Sylwester Czochralski adds: “Fred and I are the two living relatives who speak English and who actually work in technology and benefit from our relative’s foundational work in electronics and the computer industry. We feel we’re best able to amplify the story of this remarkable man.”

Schmidt says a script for a feature film is underway, and it’s something that he thinks will give JanCZ’s story the boost it deserves. “The documentaries that have been done are great,” he says. “They give you a good look at how the Czochralski method has impacted our world and JanCZ’s role. But there’s so much more drama that needs to be conveyed, because it truly is a powerful story of a man’s love for his country in the face of so much adversity.”

“Being interviewed on the topic of my family and grandfather for the first time was personal and emotional.” — Fred Schmidt

“Learning about JanCZ also highlights the importance of perseverance and dedication to science, especially considering the challenging circumstances under which he worked,” Czochralski says.

2013 was declared “The Year of Czochralski” in Poland. In 2019 the Institute of Electrical & Electronics Engineers, the world’s largest electrical engineers association, with over 440,000 members, honored JanCZ with its highest award: the Milestone. This distinction is awarded for discoveries and inventions of global significance to the development of humanity. Other recipients include Thomas Edison, Guglielmo Marconi, Nikola Tesla and Alexander Graham Bell. “Now that is pretty impressive company and context for JanCZ,” says Schmidt.

There’s another recent addition to the story that delights Schmidt — in 2024 JanCZ was inducted into a Polish “Academy of Superheroes” highlighting notable Poles created by the Nauka To Lubie Foundation and which will soon be expanding globally. JanCZ is pictured in a long, elegant trench coat extending a gauntlet-gloved hand bursting with brilliant greenish-blue crystals.

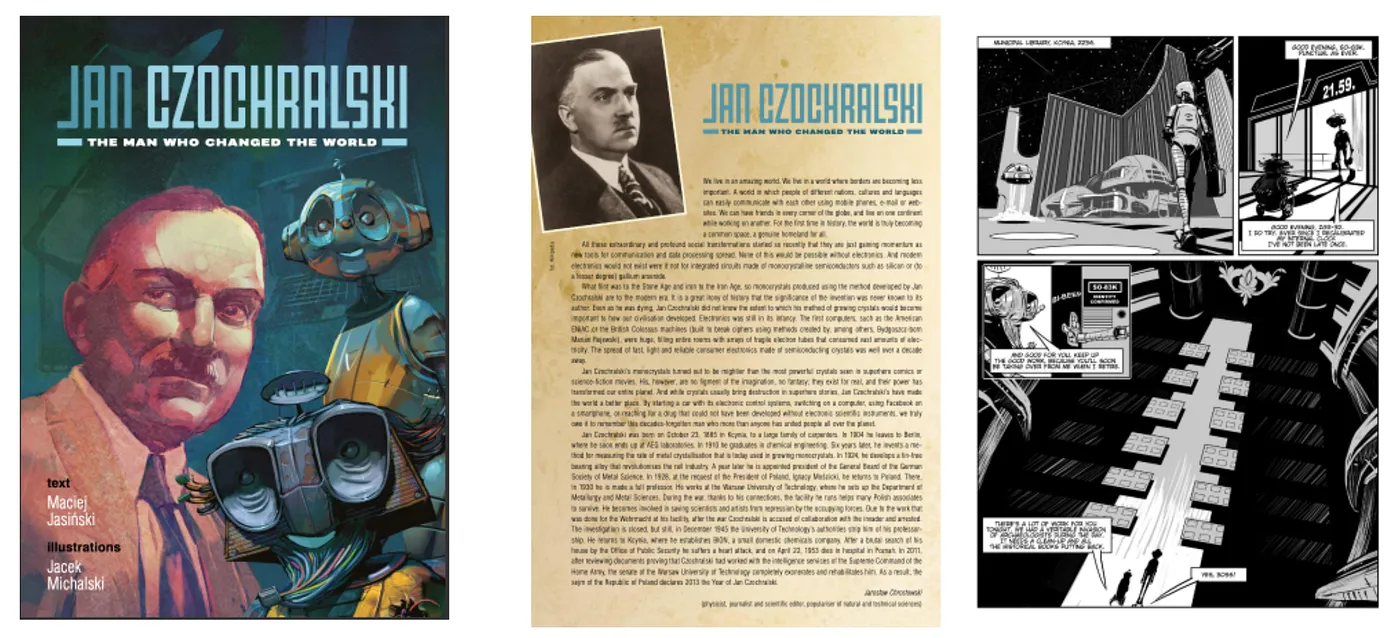

“That’s the stuff that I love, the Academy of Superheroes,” Schmidt says. “And now there’s even another whole English-and-Polish-language graphic novel adventure with some sci-fi twists that tells his story. Those are the beginning of the contemporary pieces that I want to feature on our website. They are relevant to a younger audience, to telling the story beyond a giant historical biography or compendium of his scientific work written in Polish. We’re going to make JanCZ cool.

“By recognizing his achievements,” says Schmidt, “we not only honor his legacy but also inspire future generations to pursue scientific exploration, regardless of the obstacles they might face.”