Official Website of JAN CZOCHRALSKI, Forefather of The Silicon Era

This essay is a hypothetical scenario — a fictional narrative that imagines what JanCZ’s future might have looked like had he chosen to go to work in the U.S.A. in 1928, rather than return to his native Poland. I have applied my own approach and experiences with career decisions as a seasoned business professional to guess what alternative directions my grandfather might have followed – then followed the path of his CZ Method discovery on its actual historic journey into the electronics and computer industries. As the reader can contemplate alongside me, this would have led to a very different outcome in the second half of JanCZ’s life.

-- Fred Schmidt, 2025.

What if, in 1928, Jan Czochralski made a different choice in the biggest decision of his career and personal life up to that point: ...What if he accepted the research position he was offered to work alongside Henry Ford at the Ford Motor Company in Detroit? ...Rather than the request from Poland's President Ignacy Moscicki to return to his homeland and join the academic and research staff of Warsaw Polytechnic? ...How much differently might his life have turned out?

A few years after WWI, the "Golden Twenties" began to take shape in Germany and it was in this period that Jan Czochralski was able to excel in the focus and value of his work in the commercial world.

He monetised several of his inventions; he wrote and published papers on several other discoveries he had made; and delivered talks to the scientific and academic communities. One of those new discoveries was a process to grow monocrystals — a very interesting methodology, but neither Jan nor others knew yet what to do with it. More research and experimentation would be required.

The invention that really took hold was Jan's creation of so called "Bahnmetal", or Metal B, a much less costly and far more durable alloy substitute for the tin that was used in making bearings for various transportation systems, particularly railroads which were dominant in that period. Metal B enabled trains under heavy loads to travel at high speeds and contributed to the expansion of railways everywhere, and Jan was able to land some large contracts for Metal B production. His team found markets in Germany, Poland, the UK, and even the Soviet Union and United States, where they were able to license the technology. The money came flowing in.

Life was good. Jan was able to afford a large home for his family in Frankfurt, several nice cars, a chauffeur, house staff to help with the kids and the chores, and vacations to Switzerland and the shores of the Mediterranean.

In 1923, Jan received an unexpected surprise: an invitation from Henry Ford, an industrialist at the peak of his power and who was rapidly scaling an automotive industry from his home base in Detroit, Michigan, in the United States. During the expansion of their assembly plants internationally, particularly into Europe, Ford's team had taken note of Jan's work in metals and transportation and thought there might be some opportunities for collaboration — or an even closer working relationship. Without hesitation, Jan and Marguerite decided to accept Mr. Ford's invitation — after all, they could leave the kids with their competent staff – and they booked passage from Hamburg to New York City on the UK's Royal Mail steamship "Ohio" for a November 7th departure.

The Czochralskis had a wonderful time enjoying New York City for the first time as it energized and fueled their passions for art, music, culture and high society. But after a short time, they had to continue onward to their primary destination: Detroit.

The Ford Motor Company was the unquestioned leader in the American auto industry, producing more cars than all other brands combined. The Model T was so popular that two million vehicles rolled off the assembly line in 1923 alone, thanks to Ford's revolutionary mass production techniques which reduced manufacturing costs so much that it made the car affordable for the average American. By the following year, Ford Motor Company's market value exceeded $1 billion for the first time.

Jan had some close family ties to the Detroit and Chicago areas, as two of his older sisters had emigrated there in recent years as both major cities were economic powerhouses and boasted growing communities of Polish expats. What’s more, three of his aunts had left Poland years earlier, as part of "The Second Wave" of Polish settlers to the Brazos Valley of Texas, seeking opportunity.

Jan returned to Frankfurt to contemplate his future while continuing to excel at his scientific work. But he kept in regular contact with his new colleagues at Ford, and at the same time entertained a variety of other interesting and attractive offers from across Europe as his reputation and network grew.

Then, in 1927, another unexpected but very compelling invitation arrived, this time from Ignacy Moscicki, a fellow Polish chemist who had just ascended to the Presidency of Poland the prior year. He was asking whether Jan might consider returning to Poland at some point, to Warsaw, and become involved in the business and academic communities there?

As Jan's children were all now of school age, Poland, culturally, was weighing ever greater on his heart and mind. He wanted his children to have more exposure to his – and their – Polish heritage, which was not possible deep in the middle of Germany. And Poland had now, once again, regained its freedom as an independent nation – the first time in well over a century. So the Czochralskis loaded up the family cars and set off for an extended visit to Poland.

While in Warsaw, Jan was wined and dined, taken on tours of Warsaw Polytechnic University, dazzled with offers of presiding over his own state-of-the-art research laboratory for chemistry and metallurgy, and even enticed with the possibility of being awarded an honorary doctorate degree. Meanwhile, his wife and children, none of whom had much exposure to anything Polish thus far in their lives, were given the full VIP treatment as they were whisked to museums around the city, visited the best neighborhoods and schools, and immersed in the stories of Polish history and accomplishments. No doubt it was a very complete and effective sales job by the Polish President and his team.

By the time the family returned to Frankfurt, Jan and Marguerite had a lot on their minds with some serious decisions to make about the future direction their lives would take. Just to add even greater pressure, waiting for them upon return was yet another letter from Henry Ford, with an even more fabulous offer of a prominent research and development role at Ford, possibilities for deep university engagements, and a compensation package not available anywhere in Europe at that time. Then there was also the lure of the Polish community in Detroit and family nearby. Was this the opportunity and adventure of a lifetime – far too good to pass up?

In only a matter of weeks, the Czochralskis were off to America.

Jan arrived in Detroit just at the tail end of the Roaring Twenties, with sufficient accumulated wealth to purchase a stately mansion overlooking Lake St. Clair in the poshest area of the city, Grosse Pointe Shores, just down Lake Shore Road from Ford himself and other industrial magnates. Their children were enrolled in the finest private schools and took immersive Polish language and cultural lessons on weekends. And given the direct association with Ford, Jan was immediately accepted into the top echelons of Detroit and American business and social circles.

How might Jan have fared during the Depression years? Similar to Ford and others of that class. Better than many of them, in fact. Since he was new to the U.S., unlike his wealthy and influential peers he was not yet invested in the stock market. This served him well when The Big Crash hit in 1929, a year after his arrival.

Jan immersed himself in his work, as he always did, and continued a steady output of discoveries, inventions and patents to accelerate the auto industry as well as others. For the entirety of the 1930s, he expanded his reputation and his network among the elite of U.S and European business, government and academia.

In 1939, when WWII broke out across Europe, beginning with the invasion of Poland by Germany, Jan was incensed by the audacity and magnitude of the destruction of his homeland by the neighboring country where he had forged his career. For him this conflict was deeply personal, as it hit right at the core of his overwhelmingly Polish, but partly German, being.

He immediately reached out to his contacts in Washington, D.C., to offer help to the Allied Forces. Because of Jan's unique background as a scientist, fluent in German, well-versed in German industry and thinking, and long acquainted with top tiers of German government and military, the U.S. President and Defense Department were very happy to accept his assistance. By 1942, when the U.S. officially entered the war itself, Jan had taken leave from his position at Ford to work closely with American and Allied Intelligence Services in highly classified roles to counteract German advances. Essentially, he embedded himself into Washington, D.C., and very little is known, written or recorded about this period due to national security restrictions. Jan's family saw little of him during this time – just enough to know that he was safe and working on behalf of his beloved Polish homeland, his newly adopted country of America, and involved in the race to save a free, independent, and diverse Europe.

The last half of the 1940s was a hard and complicated period for everyone everywhere, rebuilding both physically and emotionally from the profound impacts of that global war. For Jan, he again turned his attention to science to try to pick up where things left off several years earlier. But he found that he had lost interest in applying his talents and energy to the transportation industry.

During his time working with the intelligence services, he had been exposed to a wide array of the latest electronic and communication devices being developed. He had become highly intrigued by this burgeoning new market segment, and so he made another career-altering decision: to give up his prestigious and lucrative role with Ford Motor Company. With his children all now grown and living their individual lives, it gave Jan and Marguerite the freedom to take some new risks and pursue fresh adventures.

While seconded to the U.S. government, he had met and worked alongside other brilliant scientists from Bell Labs like William Shockley and Gordon Teal, developing technologies vital for the war effort like radar, guidance systems for weapons, synthetic materials, and cryptography. The war period led to significant growth at Bell Labs, with their staff doubling in size. So when Jan was offered the opportunity to join Bell in a full-time research capacity, he jumped on it.

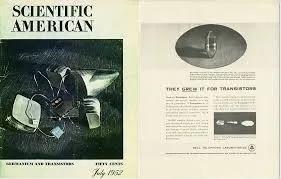

During his time at Ford, Jan had continued to experiment with and refine his process for growing monocrystals, a discovery he had made back in 1916, and he had written multiple papers about it for the scientific community. He believed that his “CZ Method” of growing crystals might have applicability to the work being done at Bell on developing the transistor and prototyping integrated circuits. It turned out he was right about that, and over the next six years he worked closely with Shockley and Teal to perfect the growing of high-quality crystals that were essential for manufacturing grown-junction transistors. This application of the CZ Method was a pivotal step in the advancement of transistor technology, paving the way for widespread adoption of these crucial electronic components.

In 1956 the Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded to William Shockley, John Bardeen, Walter Brattain and Jan Czochralski for their work on semiconductors and the invention of the transistor. Importantly, Jan was now finally able to patent his unique process for growing crystals, a move which subsequently opened a floodgate of new income streams to the Polish inventor just as his royalty income from Metal B was beginning to wane as the rail industry itself was in decline, giving way to new forms of transportation like trucking and airlines.

A few years earlier, Jan’s Bell Labs friend and native Texan, Gordon Teal, made a decision to return to his beloved home state to join Texas Instruments. Not long afterward, Teal persuaded Jan to join him to work on development of the first commercial silicon transistor. At TI, Jan was also able to assist Jack Kilby to perfect the integrated circuit in 1958. It was not a hard sell as Jan had been corresponding with some of his own family living in Texas since the late 1800s and so he was intrigued by the state and many of its similarities to Poland.

Jan came to visit TI’s HQ and labs in Dallas, less than a three-hour drive from the Texas town of Anderson, where some of the Czochralski family had settled in the Brazos Valley. While there, he also learned about the extensive history of Polish settlers in Panna Maria and Bandera near San Antonio, and the sizable Polish community in Houston. That was all he needed to justify the move, as staying connected to his Polish roots was very important to Jan at this point in his life, having achieved plenty of fame and fortune in his new adopted country over the past 30 years.

Jan, now 75, was feeling happy and settled in his new Texas life, both personally and professionally. He officially retired from TI but remained deeply involved in the further refinement and applications of his monocrystal growing techniques in the electronics industry as a consultant, principally for Fairchild Semiconductors in Santa Clara, California, which had formed in 1957. After all, Jan was a leading expert in the chip creation process, given his discovery and evolution of the CZ Method over the prior four decades, and he was close to several of the Fairchild founders from his days at Bell and TI.

Fairchild was a leading driver of chip adoption in the production of semiconductors during the 1960s for use in the nascent computer industry which was about to explode, giving rise to the term “Silicon Valley” to describe the Bay Area south of San Francisco.

Jan was at the top of his profession and now one of the wealthiest men in the world from his chip-related royalty streams and income from other inventions. While he lived comfortably and in style, he was by no means extravagant given the vast size of his wealth, estimated to be over $1 billion, placing him in the same league as oilman J. Paul Getty, the wealthiest man of that era.

Born a man of very modest and humble means in a small Polish town, Jan never forgot his roots. He became a top philanthropist in both STEM fields and the arts. He kept homes in Michigan, Texas, California, and Colorado. Much to his profound dismay, the return to Poland — of which Jan long dreamed about — never happened due to the ongoing occupation by the Germans, then the Soviets. Jan died peacefully at his Texas ranch on October 23, 1970, at the age of 85.